News + Press

Proxy Fight in Australia

The right to speak freely. It is the foundation of democracy and a market-based economy. But it is under threat right now if the Australian Government’s proposed changes to proxy reform are anything to go by. Treasurer Josh Frydenberg and his department are on a rampage.

Mooted reforms to proxy legislation in Australia may put a muzzle on shareholders due to increased disclosure requirements between proxy advisers and fund managers.

The right to speak freely. It is the foundation of democracy and a market-based economy. But it is under threat right now if the Australian Government’s proposed changes to proxy reform are anything to go by. Treasurer Josh Frydenberg and his department are on a rampage.

Proposed changes include forcing proxy advisers to give listed companies a week’s notice before they send voting recommendations to clients (fund managers), plus, the research on which their decision is based. Also, proxy firms would have to give clients access to a company’s response.

But the most spirited proposal is a measure that would force proxy firms to be independent of super funds. That’s an instant farewell party for the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (ACSI). ACSI advises funds that control about 10% (on average) of all top ASX200 companies. Problem is that ownership of the firm lies with 36 institutional investors (mostly local industry super funds) with assets of more than $1 trillion combined. Goodbye ACSI. Is independence the sole determinant of good advice?

Other players in the proxy adviser space include Ownership Matters, CGI Glass (a branch of the San-Francisco based advisory) and ISS—majority-owned by Deutsche Bourse Group. Mr Frydenberg wants to increase the transparency of these advisory firms in a misguided attempt to increase the transparency and accountability of proxy advice. Why? They are considered too influential when it comes to corporate governance in Australia. And we have a high degree of institutional investment in Australia owing to compulsory super.

A Driver’s Licence

The fact none of these advisory firms require a Financial Services licence is another point of concern for Treasury and company directors. Going forward, this might change. A Treasury consultation paper says there is “insufficient public information today to determine whether superannuation funds, in this area, are acting in a manner consistent with their legal obligations.”

Licencing aside, the proposed changes to the regulation of proxy advisory firms all add up to more costs, more headaches, and sadly, less incentive for funds to stick their neck out on crucial voting issues. We can see the cushy Australian corporate director club looking on with a wry grin. Superfund members and shareholders will start to bear the cost of this heightened transparency in the form of higher fees and higher expenses for corporate governance.

The Old Days

So just when it was looking like things were changing for the better on the ASX (growing shareholder activism), it appears the days of sleepy boards and nonchalance for shareholder rights will continue.

From our point of view, there is simply no evidence to support the grievances of company directors who believe they are shackled by dissenting proxy advisory firms. According to an ASIC review conducted in 2017, proxy firms recommended “against” votes in 12 per cent of resolutions put forward by ASX200 companies. Not all of them—12 per cent of them. And of the 12 per cent, only 17 per cent on average received a dissenting vote from shareholders.

Does this demonstrate a heavy-handed and unnecessary influence by proxy firms? We think not. There were also reports during the 2017 AGM season of large institutional shareholders who decided to vote against resolutions that were the subject of a ‘for’ recommendation by proxy advisers. This is consistent with representations made to ASIC by institutional shareholders that they do not follow proxy advisers’ recommendations automatically.

Further, a recent article in the Financial Review showed 96.2% approval for 7,500 non-executive director elections over the past decade. Only 6 candidates were defeated. And “no board of an ASX 300 company has been spilt following a second-strike vote, and of the 1321 resolutions proposed by ASX 200 companies in 2020, only 36 votes went against the company.” Yes, a grand total of 36.

Follow the Leader

It seems we are walking in the footsteps of US Securities Exchange Commission who last year introduced reforms requiring proxy materials be filed early to give companies time to respond to proxy recommendations and requiring proxy firms to disclose any conflicts of interest (like reforms introduced in Britain a year earlier).

Proxy advisers in Australia have obligations under the Corporations Act to ensure any financial services are efficient, honest, and fair, while they must not mislead or deceive in any activity. Let’s hope it remains that way.

Otherwise, we see shareholder rights being weakened, with a shaky and generic superannuation fund voting system to follow. A diversity of views is surely an essential component of good governance. If those views are cancelled then we are taking a step backwards, not forward.

Australia does not have any protections of free speech by law, but this does not mean it should reduce the ability of advisors and their funds to cast their opinion. The Member for Kooyong, please let market participants speak freely when it comes to corporate governance.

The Activist Tackling an Oil Giant

Exxon Mobil is a big company. It has a market cap of about US$260 billion. Australia’s mining giant, BHP, has a market of US$185 billion in comparison. So when you make a declaration to challenge one of the biggest companies in the world then you’d want to be sure of yourself. A new hedge fund formed in December 2020 appears to have this surety in spades.

How a minnow activist is tackling complacency inside a titan of the oil industry.

Exxon Mobil is a big company. It has a market cap of about US$260 billion. Australia’s mining giant, BHP, has a market of US$185 billion in comparison.

So when you make a declaration to challenge one of the biggest companies in the world then you’d want to be sure of yourself. A new hedge fund formed in December 2020 appears to have this surety in spades. The fund goes by the name Engine No.1 and was founded by an investor named Chris James— along with two other veterans of the hedge fund industry.

Some Clout

According to Engine No.1’s website, Chris has a history of building “asset-heavy companies in industries in transition.” He’s also been an investor in the tech sector for nearly three decades.

Prior to Engine No.1, Chris was the founder of Partner Fund Management (PFM) and co-founder of Andor Capital Management. PFM is based in San Francisco while Andor is a VC fund based in New York.

Andor was shut down in 2016 by co-founder Daniel Benton—the second time in a decade the fund had been shut down (the fund was also shut during the GFC in 2008). The firm had a successful run for 15 years though and Benton now runs his own private family office called Benton Family Office.

Benton has been described as, “one of the top technology investors of his generation.” But what of Chris James? He is the main man taking on Exxon Mobil after all.

Well, Chris has built a career growing companies from the ground up in multiple industries it seems. Not only multiple industries, but industries in the process of long-overdue transition—like oil & gas.

Widening Scope

The major theme Chris has noticed during his career to date is ‘too many companies who fail to factor in external forces—like their impact on the environment. He believes a company’s performance and its broader external impact are ‘intrinsically linked.’

A natural target for this view and Chris’s new fund is oil giant ExxonMobil.

You could argue no public company in the history of oil and gas has been more influential than ExxonMobil. To give some context, the company was the largest company in the world by market cap only 10 years ago. It was the largest company in the Dow Jones Industrial Average for a long time too. Prior to Engine No.1’s latest campaign though, ExxonMobil’s market cap has halved, and it has been booted from the Dow Jones all together.

And all this sloth against a backdrop of growing oil and gas demand the past decade. Engine No,1 in its capacity as a new breed of shareholder activist believes ExxonMobil has been bereft of a ‘credible strategy to create value in a decarbonizing world.’

Changing Tide

One thing is clear, the industry and the world ExxonMobil now operates in are changing. ExxonMobil must change as well.

We think Engine No.1 might be onto something in this case. Of note is the fact Engine No.1 has achieved almost immediate results after sending a letter to Exxon’s board on December 7, 2020.

Chris and his team went straight for the jugular. They demanded a new focus on clean energy and changes to the 12-member board of directors at Exxon. It was a bold move for a company with just a 0.02% stake in a $260 billion company.

A Rebuttal

The ExxonMobil board refused to commit to a carbon-neutral strategy after reviewing the letter. And the arm wrestle began. Engine No. 1 formally launched a proxy battle in March 2021 with a view to forcing a change of direction.

All this from a small activist born months ago, against a company who can trace its history back to 1870, when John D. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company.

Engine No.1 has since secured two crucial board seats in a huge win for the activist. It wants four seats in total but two is a good start. Their other objectives? They want ‘corporate governance reforms, a review of Exxon’s climate action plan (and its impact on the company’s finances) and greater public disclosure of its environmental and lobbying activities.’

That is a big roster of changes. But even before the vote, Engine No.1’s campaign was clearly having an influence on Exxon. In the past few months, ‘Exxon has proposed a $100 billion carbon capture project in Houston and committed $3 billion to low-emission technologies through a new venture,’ according to news site Penn Live.

Exxon denies any of these investments were due to pressure from Engine No. 1. That is hard to believe.

These are some of the biggest investments Exxon has proposed in sustainability in recent years, and they came right after Engine No.1 popped on the scene and post the election of a new U.S. president who has made fighting climate change a priority.

Pensions Onboard

Engine No.1 has also elicited support from other major Exxon investors, like the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and the New York State Common Retirement Fund. Both these pension funds have been laying pressure on Exxon to do something about its lagging (non-existent) sustainability strategy for some time now.

But who really cares you might say? All this demand for change is straight out of the hedge fund playbook, right?

Well, yes. But the difference, in this case, is the emphasis Energy No.1 is putting on sustainability and a clear connection between sustainability and long-term profits. And it makes a strong case that the reason Exxon’s financial position has been deteriorating is because of its failure to invest in low-carbon technologies.

Exxon has clearly been focusing on short-term gains from fossil fuels at the expense of its long-term future in a global economy. The economy now puts a premium on sustainability and a penalty on carbon-intensive activities like the production of oil & gas. The switch to long-term gains in favour of short-term profits is long overdue.

Adding might to the fight, the willingness of U.S. pension funds and BlackRock ($7.4 trillion in assets under management) to support Engine No.1 shows the tide is turning. The Exxon board might finally be waking up as a result.

David vs. Goliath?

The significance of David taking on Goliath may not be the story here after all. Is it more about the sheer weight of activist funds leading pension funds toward sustainability?

Either way, companies and executives that fail to invest in the transition to low-carbon energy will increasingly risk the assault of hedge funds and pension funds (super funds in Australia). And Super funds are armed to the brink with a continuous flow of money that may choose to tail the efforts of activist investors.

Despite its initial pushback against Engine No. 1, the board of directors at Exxon Mobil has clearly been shaken. The flood gates may be opened on other industry laggards who are yet to articulate how they fit into a global economy with a firm eye on sustainability.

Why Shareholder Activism Remains in its Infancy in Australia

Investors on the ASX feared an all-out assault when BHP Billiton was raided by an infamous New York-based hedge fund in April 2017. But the attack from Elliot Management failed to spark any major revolt among retail or institutional investors. And the introduction of new investment managers focused on activism has been tepid.

Investors on the ASX feared an all-out assault when BHP Billiton was raided by an infamous New York-based hedge fund in April 2017.

But the attack from Elliot Management failed to spark any major revolt among retail or institutional investors. And the introduction of new investment managers focused on activism has been tepid.

In fact, you could argue there are less than a handful of true activists in Australia to this day. They include the Tenarra long-short funds, the 360 Capital Active Equity Value Fund, Sandon Capital, Viburnum Strategic Equities, and Armytage Microcap Activism Fund.

You could throw in other part-time activists who allocate a smaller piece of the pie to activism. Doing this would include the likes of Geoff Wilson’s Wilson Asset Management, Allan Gray, Perpetual Limited, Tribeca Investment Partners, and VGI Partners.

Still, less than a dozen activist managers all up. Of course, there is a lot of influence behind closed doors in corporate Australia. But it is impossible to track. We will leave the shadow influence out for now.

Why Not More?

Well, there are three major reasons we believe activism remains a dark horse in Australia. They include:

An unhealthy acceptance of underperforming management teams among fundies and investors

A level of ‘corporate caginess’ among managers when it comes to transparency

A lack of support for managers who have been inserted as would-be activists on the boards of listed companies

These problems exacerbate in the form of little marketing of shareholder activism as a strategy. Or even a viable segment of investment management. Throwing all this into a pot means you’ve got an industry lagging its big cousin in the U.S.

In our defence, we are second in the world when it comes to activism. Even Japan (11 campaigns in the first quarter of the year) cannot match our level of activity (12 campaigns) despite the size of their market (Japan has a market of US$5.7 trillion vs the ASX at US$2.8 trillion).[1]

A Long Road Ahead

The tinder is flaming on the ASX you might say with favourable laws in place like the two-strikes rule and a 5% vote required for an EGM, but we have a long way to go.

Research by the lead trackers of activism across the globe, Activist Insight, found there were 62 activist targets in Australia in 2020, well down on 2018's record of 81 targets and down more than 10% from 2019 (73).[2]

At least two-thirds of the actions were board-related and were mostly isolated cases of outrage against generous performance and pay incentives.

Only 10 percent of targets were called out on issues regarding business strategy. As above, 10 percent might be understating the extent of rumblings behind closed doors between shareholders, management, and boards.

More Talking Please

One thing is clear though: the advent of Australia's two strikes rule, which can trigger a board spill if more than 25 percent of shareholder votes reject the remuneration report two years in a row, has forced directors to increase their dialogue with shareholders. Some directors like this. The majority don’t (especially where an entrepreneur-founder is non-existent on the board of directors).

But this new rule has created a grey area for the scope of shareholder activism and its definition. Going after a campaign based on pay and bonuses is reactive and therefore not a true form of activism. Why? Reacting to events ex-post does not unlock material value in a proactive manner. That is the whole point of activism.

Remuneration campaigns are short-term fixes as well. Any dispute is typically settled by way of shareholder rights provisions that exist in Australia.

In contrast, true activist campaigns tend to focus on structural and/or strategic issues. In most cases, these actions have a more significant impact on value creation for all stakeholders in a listed company.

Looking Way Down the Road

True activist campaigns are proactive in nature almost always take a long time to implement. A high degree of expertise and staying power is required for shareholders and management to achieve their desired outcome as well.

The key is changing the perception of activism and showing boards how effective an activist campaign can be in the presence of an open dialogue between key stakeholders.

Gone are the days of the corporate raider. The modern shareholder activist is making the transition from ‘thorn in the side’ to trusted confidant and value creation specialist.

May we see more activist campaigns running on the ASX soon.

[1] Data from Insightia report, “Shareholder Activism in Q1 2021” and Wikipedia.

[2] Data from Insightia report, “Shareholder Activism in Q1 2021.”

Why the ASX is Ripe for Shareholder Activism

Gone are the days of the corporate raider stripping assets from profitable companies in the name of personal profit. The new kid in town is the shareholder activist. Activists are relatively new (in the history of financial markets) but highly influential players when it comes to listed securities. Their strategies and actions are wide and varied.

Gone are the days of the corporate raider stripping assets from profitable companies in the name of personal profit. The new kid in town is the shareholder activist. Activists are relatively new (in the history of financial markets) but highly influential players when it comes to listed securities. Their strategies and actions are wide and varied.

In fact, activists are growing by the dozen if recent data are anything to go by. Figures from a Credit Suisse report published in 2019 show the number of activist campaigns ballooned in the decade from 2009 to 2019 from 25 to 930 at the end of 2018.[1] And for the first half of 2019, the figure was already sitting at 646.

Activity has slowed a lot since the onset of a pandemic, but momentum is starting to build again. Evidently, you could say the main distinction between the activist and the corporate raider is the intent to work in a constructive manner with listed companies to realise shareholder value. They can still be the proverbial ‘thorn in the side’ but in a much nicer way.

The ASX… Ripe for the Picking?

While the level of shareholder activism in Australia pales in comparison to the U.S. (169 campaigns in the U.S. in the first three months of 2021 versus 12 on the ASX)[2], we still have the second most active market in the world for activism (just ahead of Japan). There are three main factors driving this activity down under including:

The ‘Two Strikes’ Rule on the ASX

This rule allows just 25% of shareholders to vote down a company’s remuneration report and ultimately spill the board of directors (there is no such tool for activists in the U.S.)

Only a 5% vote to call an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM)

Adding to this rule, recent amendments to regulatory guidelines now allow shareholders of ASX-listed companies to talk to each other about company performance.

Large Institutional Shareholdings

This is self-evident given the size of our superannuation pool. Back this with a strong media presence which can quickly affect the reputation and share price of companies in a matter of minutes.

Picking on the Little Kids

The market cap of companies engaging in activism on the ASX is skewed heavily towards the nanocap end of the market (42% in Q1 2021) with an increasing focus on board-related activism (47% of demands in Q1 2021).[3] While the bias for picking on the little kids has always been present in the Australian market, there have been short periods where activity has migrated to large caps. A good example was the period from 2014-217. That trend reversed sharply in 2018 though and has continued since then.

Obviously, size matters in terms of any news getting picked up by the media, so the nano and micro-cap stocks who end up in the crosshairs of shareholder activists barely register a blip in the major metro news columns—unless there is a particularly salient angle or agile media professional supporting the efforts of activists.

The media trend is starting to shift with some large caps making headlines in the first quarter of 2021. They include Woodside Petroleum, Tabcorp, Santos, Rio Tinto, AMP, and Bank of Queensland, and others. We expect this increased share of media coverage to continue as activists stake their claim on the ASX.

Looking Forward at Shareholder Activism on the ASX

The current stats say a lot about the level of activism in the U.S. versus Australia and the rest of the world. You could almost say activity is non-existent outside the US based on the figures above. But the two-strikes rule and other regulations on the Australia Stock Exchange (ASX) are clearly a stimulant for activity in our own backyard. Watch this space for some exciting (constructive) battles ahead.

REFERENCES

[1] Data from Credit Suisse 2019 Fourth Quarter Corporate Insights report titled, “Shareholder Activism: an evolving challenge.”

[2] Data from Insightia report, “Shareholder Activism in Q1 2021.”

[3] Data from Insightia report, “Shareholder Activism in Q1 2021.”

UPDATE: Shareholder Activism in Australia (Q1 2021)

It’s been slow going for shareholder activism across the globe so far in 2021. The coronavirus pandemic put a dampener on activity during 2020 and continues to make its presence felt. Activists have become a little gun shy it seems as companies deal with the ongoing fallout from the pandemic.

It’s been slow going for shareholder activism across the globe so far in 2021. The coronavirus pandemic put a dampener on activity during 2020 and continues to make its presence felt. Activists have become a little gun shy it seems as companies deal with the ongoing fallout from the pandemic.

Despite this, Australia was second only to the US in terms of overall activity. Companies making headlines with activists on the ASX included Woodside Petroleum, Tabcorp, Santos, Rio Tinto, AMP, Bank of Queensland, among others.

Data from London-based research firm Insightia make the picture clear though. Their recent report covering the first quarter of 2021 shows[1] :

The overall level of activist activity across the globe was the lowest in the past seven years with 247 companies publicly subjected to activist demands (versus a high point of 385 in the first quarter of 2016).

Activist activity continues to be highest (by a stretch) in the US, followed by Australia and Japan.

In the US, 169 companies were targeted.

The next most active regions were:

Australia (12 companies targeted)

Japan (11 companies targeted); and

Canada, UK, the Republic of Korea (all with 8 companies targeted).

Activity was lowest in Malaysia, Austria, Finland, Czech Republic, and New Zealand (all had only one company targeted during the period).

Figure 1: Australian Activist Targets SOURCE: Activist Insight report from Insightia

The stats say a lot about the level of activism in the U.S. versus Australia and the rest of the world. You could almost say activity is non-existent outside the US based on the figures above. But the two-strikes rule and other regulations on the Australia Stock Exchange (ASX) are clearly a stimulant for activity in our own backyard.

The basic materials and technology sectors on the ASX were the most targeted. Each sector accounted for 25% of the overall total number of companies targeted. In terms of demands on ASX-listed companies, demands on boards were the most common, accounting for 47% of demands overall.

In addition, activists in Australia have so far secured six board seats. 50% of these board seats were secured through settlements.

Going After the Nano Caps

Nano caps on the ASX are copping the brunt of shareholder activist demands and appear to be sitting ducks for larger fund managers who can influence a vote with a minimal investment relative to the size of their funds under management.

The following graphic makes this clear:

Figure 2: Nano caps still account for more than half of activity happening on the ASX but demands are still well below prior quarters from the last three years. SOURCE: Activist Insight report from Insightia.

Having an Impact

Of note from Insightia’s report was the number of impactful campaigns by Australian companies in the first quarter.

The average impact versus total campaigns launched averaged 25% over the past five years but this figure is already at 50% after the first quarter of 2021 (6 out of 12 campaigns were considered ‘impactful’ by Insightia data).

Figure 3: 6 out of 12 campaigns launched in Australia in the three months to March had a direct impact on listed companies.

Providing Some Definitions

Providing some clarity in Insightia’s first-quarter report were the definitions they provided at the beginning regarding shareholder activists.

These definitions may help to clarify where Advocate Strategic Investments (ASI) sits among the global cohort of activists. The definition of an activist was spread among three categories:

PRIMARY FOCUS ACTIVIST: AN INVESTOR WHICH ALLOCATES MOST, IF NOT ALL OF ITS ASSETS TO ACTIVIST STRATEGIES.

PARTIAL FOCUS ACTIVIST: AN INVESTOR WHO FREQUENTLY EMPLOYS ACTIVIST INVESTING AS PART OF A MORE DIVERSIFIED STRATEGY.

OCCASIONAL FOCUS ACTIVIST: AN INVESTOR WHO EMPLOYS AN ACTIVIST STRATEGY ON AN INFREQUENT BASIS.

We have bolded the definition that best suits ASI. We plan to work constructively with listed companies on the ASX to help shareholders realise long-term value in their shareholdings.

REFERENCES

ASI's Investment Mandate & Philosophy

ASI is an Australian-based alternative-style equity investment manager employing and managing a proprietary investment strategy called the ‘Constructivist Investment Strategy’. Steering the company is ASI’s founder, Michael de Tocqueville, who together with ASI director Henry Wolfe have several decades of experience in shareholder activism in Australia, the US, and Canada.

ASI is an Australian-based alternative-style equity investment manager employing and managing a proprietary investment strategy called the ‘Constructivist Investment Strategy’.

Steering the company is ASI’s founder, Michael de Tocqueville, who together with ASI director Henry Wolfe have several decades of experience in shareholder activism in Australia, the US, and Canada.

Michael is developing a team to employ ‘deep-value private equity style research’, to identify listed companies where value has been eroded due to one or more of the following reasons:

capital misallocation

managerial deficiencies

ineffective board structure

improper or misaligned executive incentives

operational under-performance

governance issues

strategic errors of scale or scope

ASI’s Motive

Shareholder activism is—at its core—a response to the potential for capital gains owing to the underperformance of publicly listed companies. The cause of this underperformance can be tied to a company’s relationship with absentee owners—the shareholders—otherwise known as agency risk.

ASI will seek to overcome underperformance issues stemming from agency risk by focusing on:

the operational aspects of company management

advocating changes in board structure

the dislodgement of underperforming managers

challenging ineffective strategies, and

making sure that merger and control transactions make sense for shareholders.

In so doing, as the evidence shows in most cases, ASI will aim to enhance the value of companies for all shareholders. ASI’s directors have worked with (or engaged with) many companies, boards, and management in the past and will engage with more in the future.

ASI’s Strategy and Approach

ASI’s approach to investment is active value driven from a traditional investment point of view. We make use of the following styles and components of value investing:

Active Private Equity style, with

Constructive shareholder engagement

These are the primary investment oversights we employ to maximise value and we conduct extensive screening to identify potential targets.

Our focus is on companies that are easy to understand. Employing this philosophy means we may pass up on a good number of opportunities for potential investment.

We apply a disciplined, bottom-up, strategic financial evaluation and valuation processes with a long-only strategy. We have the discretion to apply shorting strategies, however only in unique cases where it may be a strategic requirement.

Please note we will maintain significant shareholdings in only 3-5 highly attractive activist opportunities at any one time. We may hold a sub-portfolio of passive investments in a portfolio to generate yield when opportunities are limited or to balance the risk of existing holdings in more strategic investments.

We are benchmark unaware and don’t seek to have any correlation with an index. We will be marked against the Reserve Bank of Australia's (“RBA”) cash rate with an added equity risk premium. Our return target is an annual rate of return on capital of 15% over the medium to long term.

Where Do We Find Our Targets?

A company may become a target of ASI for a variety of reasons but generally, most targets exhibit two characteristics:

they show good operating performance but are fundamentally undervalued; and

the activist perceives some change in the capital structure, strategy, and/or governance of the target that, if implemented, has the potential to “unlock” value for shareholders.

Who are ASI’s Clients?

ASI’s client base, as our AFSL permits, is limited to High Net Worth (“HNW”) and Sophisticated Investors, as defined by the Australian regulated Corporations Act 2001.

How ASI operates the Constructivist Strategy

The Constructivist investment strategy is delivered to client investors via a managed investment strategy (“MIS”). ASI as a principal investor, or an investment manager, acquires shares in target companies through its Prime Broker Interactive Brokers (“IBKR”).

Shares acquired by ASI, are held in the names of its clients with ASI’s prime broker IBKR who in turn lodges the holdings with an independent custodian, BNP Paribas Group (“BNP”). Clients have complete online access to their portfolio from IBKR, which also provides administration reports as required which can also be viewed online or printed.

As far as management fees are concerned. ASI earns its revenue through enduring portfolio management fees over the life of the client accounts managed by it. The managed accounts—depending on the type of client—will have mandatory lockup terms for the purpose of not disturbing the constructivist equity strategy.

As mentioned previously, the client mandates are only entered into with wholesale investors as defined under the Australian Corporations Act 2001 (“Act”). ASI’s revenue base is made up of a portfolio management fee of 1.8% plus a federal goods and services tax (“GST”) of 10%. The management fee is paid monthly in arrears. There are no additional client administration or custody fees charged.

ASI is also entitled to a 20% performance fee plus GST of 10% (also known as carried interest). The performance fee is subject to a high-water mark which ASI has currently set at 10%. The performance fee is calculated annually. That fee is also subject to review and amendment at any time, with three months’ notice given to clients.

For more information, please contact us today.

Looking Back at 2020 & What’s In Store For Shareholder Activism in 2021?

To say the coronavirus pandemic had a sudden and devastating impact on our health and economic prospects during 2020 would be an understatement. The booming industry of Shareholder Activism was not spared the wrath either. As companies all over the world tried to patch leaky holes at the infancy of the pandemic in February and March, activists chose to hit the pause button.

A Year We Won’t Forget Lightly

To say the coronavirus pandemic had a sudden and devastating impact on our health and economic prospects during 2020 would be an understatement. The booming industry of Shareholder Activism was not spared the wrath either.

As companies all over the world tried to patch leaky holes at the infancy of the pandemic in February and March, activists chose to hit the pause button.

Many were afraid of looking like vultures against an ugly backdrop of a damaging health and economic crisis. Volatility in the share market, uncertainty about our economic future and a ‘go-slow’ approach to M&A stopped most activists in their tracks.

The slowdown in activist activity may have come as a relief for many CEOs and Boards. In fact, the first nine months of 2020 showed the number of U.S. companies publicly subjected to activist demands fell 11%, to 367.[1]

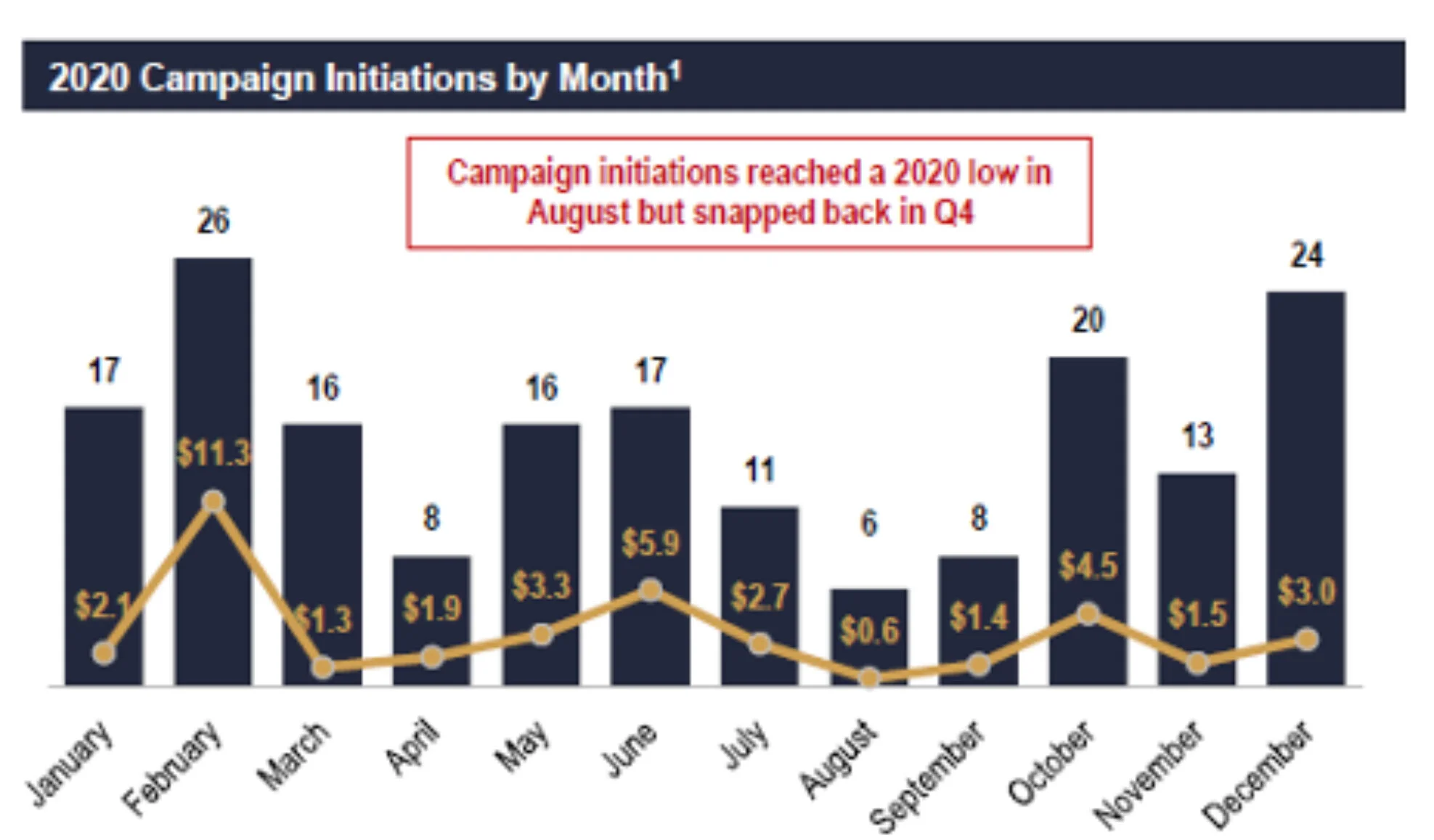

Figure 1: 2020 Global Campaign Activity and Capital Deployed ($ in billions).

Source: Lazard Shareholder Advisory Group.

But the relief didn’t last long. There were immediate signs of an uptick in activist activity once the storm settled and companies began adjusting to the crisis.

The V-bottom reversal in the stock market was most astounding. A ‘whatever it-takes’ approach from central banks helped lift share prices and put an immediate spotlight on activist portfolios in the U.S. who ‘stuck to their guns’ so to speak.

“The market’s negative response to stocks in a process of transition has since become favourable and funds that doubled down on their convictions were rewarded handsomely,” said Activist Insight in its 2020 Annual Report on shareholder activism.

Like A Bull at The Gates in 2021

We believe activists will be ready to explode into a surge of activity in 2021. Activists who did a full 180 on ambitions to launch campaigns in 2020 will now give the ‘all-clear’ on fresh campaigns. Activists can’t sit and wait forever after all. Funds who raised capital will be feeling the pressure from investors to deploy capital and show them a return too.

Who Will Be in the Crosshairs?

We see activists are focusing on companies that underperformed relative to their peers and those that showed poor judgment in response to the crisis.

Companies that continued to reward executives with generous pay packets and bonuses even as their share prices plummeted will be firmly on the radar too (a few companies that used JobKeeper payments to prop up earnings come to mind here).

Industries most likely to be in the crosshairs are those that were facing challenges before the pandemic hit, like energy and manufacturing (the ‘old’ industries). And companies that experienced a big shortfall in earnings because of the pandemic, such as entertainment and events and commercial real estate will also be a natural target.

ESG Back in Focus Too

If there was a theme for ESG in 2020, it was the ‘S’ part of ESG. It’s obvious to anyone that social issues claimed the spotlight among the public and media outlets. Social issues are the real deal in the shadow of the pandemic—especially considering the Black Lives Matter movement.

The pressure gauge will go up several notches and companies across the board will face even more pressure from activists to focus on social issues like diversity. Expect more focus on female participation at Board level and the issue of diversity among employees to be high on the list of priorities. Tokenism will no longer be excepted.

You can count on activists to step up demands on the environmental front too. This trend had a lot of salience leading up to the pandemic and will resume with fervour. Rio Tinto provided a shocking example in late 2020 of how lax ESG policies can be and the lengths a listed company will take to circumvent them.

A large sample of activists has now demonstrated the ability to go after ESG concerns. Fewer have managed to turn the movement into a working business model though and a sole focus on ESG is not going to be an objective for ASI.

The AGM and reporting season in 2021 may be a process of sorting the brains from the brawn, especially for newcomers or inexperienced activists.

Choosing the right targets, finding workable solutions, and working with boards in a constructive manner, plus a good dose of ‘street smarts’ will be more important than ever for activists heading into 2021 and beyond.

What is Activist Investing and Why is it Important?

The goal of activist investing is to initiate fundamental change and generate shareholder value improvements. Constructive activists have a high research investment spend per company, relatively long holding periods of around three to five years and high concentration in their asset mix.

Article 1

What is Activist Investing and Why is it Important?

Influence Without Control

The goal of activist investing is to initiate fundamental change and generate shareholder value improvements. Constructive activists have a high research investment spend per company, relatively long holding periods of around three to five years and high concentration in their asset mix.

An activist will typically recruit experienced industry professionals to provide knowledge about significant value drivers for a specific company or industry. In a nutshell, an activist investor is a hybrid—somewhere between a full-control model, such as private equity, and a more active or passive asset manager, such as a traditional managed fund.

A constructive activist investor's primary focus is having a significant influence on a company's plan without paying for full control like a private equity firm would. Achieving the objective goal of influence requires intelligent communication with major shareholders and the media. Resorting to costly and acrimonious public battles is avoided rather than embraced.

A thoughtfully crafted value-creation agenda based on diligent research and careful analysis of an enterprise for months at a time, if not years, is a typical scenario before investment. Practical, highly commercial collaboration with management behind the scenes is essential as well. And sometimes, the 'stick and carrot' approach is required to motivate target companies into action.

Why is Activism Important?

A shift in power between management and shareholders has ushered in an era of 'corporate management.' Shareholders, in a sense, have become disconnected from their investment as the Board of directors and senior management of listed companies continue to find ways to exert more control. Many apparent conflicts of interest arise in this situation.

Today, corporate management often acts as if they own a company. However, the law clearly states shareholders do. Management is merely an employee—a corporation's Board of Directors governs management. The Board of Directors works for and answers to the shareholders—the real owners of the company. Management frequently manipulates control of the Board of Directors (Board) by populating it with friends and acquaintances. They are honoured to become Board members, yet, afraid to voice objections due to fear of losing their position.

A "rubber-stamp" Board can lead to a host of problems. Yes, this is not always true, of course. Honest, capable, and ethical management teams endeavour to create value for shareholders daily. But the trend towards management making decisions not in shareholder's best interests continues. Typically, shareholders are not well versed about the companies they own, nor are they well informed enough to prevent or stop corporate corruption in the making.

A Way Forward with Activist Investing

Constructivist Shareholder Activism is the process of shareholders becoming involved in the governance and management of the companies they own. The key is representing shareholders and constructively working with boards, not in a hostile manner like some of the old corporate raiders.

While owning a minority of a company is typical, an Activist's goal is to create value for ALL shareholders. And many studies have shown shareholder activism produces returns superior to the overall market returns with much less risk. The Activist Insight Index, which tracks dedicated activist funds worldwide, has returned an average of 14.2% per year since 2009, against 14.5% for the S&P 500 Index and 9.5% for the ASX 200.[1]

Exposure to an activist strategy or fund offers an intelligent diversification alternative for most investors and qualifies as a healthy inclusion in a balanced fund.

[1] https://abl.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/public/Expertise/ABL-Shareholder-Activism-Report.pdf